Part I – Characters

There are great novels and awful novels, and then there are those that are in between. I call them FRUSTRATING.

They are frustrating because they could have so easily been so much more. They have major flaws and errors that are easy to spot and quick to correct, but no one bothered. These novels also often play with the established format and structure of the novel/genre and tacitly tell the reader, “You don’t matter, I write for myself.”

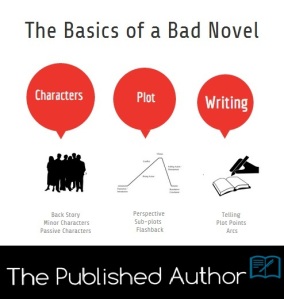

The bad novel or the frustrating novel is very common today because of the ease of publishing. In bypassing the publisher, the new author has also bypassed the editor. In this series of posts dedicated to the FRUSTRATING NOVEL, I am going to delve into three basic elements starting with CHARACTERS

I am not going to get into the principal characters (protagonist, main lead, support lead, antagonist , etc) that is a discussion for another day and a much longer one at that. Let us concentrate on the 5 main problems pertaining to characters in such novels.

- Lingering on minor characters

Naming minor characters is not really bad, but if you start naming all characters and telling us a little something about each of them, you are putting the reader in a maze. Soon he will lose track of who’s important and who’s not. You are the God of your story, if you linger too long on a minor character your reader will assume the character is important.

Let’s take a simple example:

I live in an apartment building in Manhattan. It is a group of 170 odd apartments with top of the line security and a very polite security guard.

That’s a simple description of your apartment.

I live in an apartment building in Manhattan. It is a group of 170 odd apartments with top of the line security and a very polite security guard, Andy Brown. He prefers to call himself in 007 style, “Brown. Andy Brown.”

The focus of that information is now your security guard, not your apartment. I expect your security guard will be more than just a person you pass by on your way in and out, why else would you bother to tell me about him.

I live in an apartment building in Manhattan. It is a group of 170 odd apartments with top of the line security and a very polite security guard, Andy Brown. I acknowledged his pleasantries with a nod and a smile and stepped out onto a cold sidewalk.

I have named the minor character because I have many scenes of simple interactions, but I write in a way to indicate clearly to my reader that stepping out of home is the event, running into Andy Brown isn’t.

A lot of writers do worse. They add a posse of characters to make the setting more realistic. Andy Brown is only the night security guard, Billy Green is the daytime security guard. Then there’s Andre, the Mexican kid who delivers flowers for the foyer and Kim Hau, the super-smart Asian girl who delivers groceries to your doorstep, she is doing this to save up for college by the way. These authors argue that this is exactly how it’s in real life.

Well, fiction isn’t real life. It shouldn’t be.

Minor characters are rarely fun for the writer, literally never for the reader.

- Characters from the back story

James Bond’s grandfather was a pharmacist. So what!

In building the back-story of principal characters, writers often create family trees and a slew of minor characters that bind their hero’s life story together. As arduous as that task is, it must always remain in the background. Like a backdrop it should complete the picture but never be the focus.

Every character must have a back story, what does it really mean?

It simply means that your novel is set in a finite space of time but your characters have existed before and after your novel.

If your novel is about a whirlwind romance between Tom and Betty from 1979 to 1982, you have to be clear in your head as to what they were doing before 1979. Many of those events and incidents would have added up to make them the way they were in 1979. The important thing is: it should be in your head, not necessarily on the page. The character’s action could well be a direct or indirect result of the back story but if you have to keep visiting the back story for every trait or reaction and in the process produce an ensemble of blink-and-you-miss-it characters, you will dissipate the tension and cause the reader’s mind to wander. No author wants that.

Let’s again take an example

The hero has grit. He comes from a long line of renowned hunters who have stared death in the face and defeated the most ferocious of beasts. How do you highlight this lineage to give more depth to your character?

- If your hero having grit has nothing to do with the plot, then let’s leave it out. If your story is about, say, your hero struggling to clear his SAT, then any reference to his hunter ancestors or an attempt to liken them killing a tiger to him killing the monster that is AP Trigonometry would be stretching it too far. Don’t try to connect what cannot be connected.

- Get another character to refer to his ancestors but not in a matter-of-fact way, it should be done in a scene that directly connects to the information. For example, your hero is a doctor working on a resection. You can liken his grit in ridding the body of a tumor to that of his ancestor who chased a man-eating tiger out of the village. Don’t just drop information; make it connect to the story.

- Let the author/narrator refer to these ancestors multiple times throughout the book or the sub-plot but each time you refer there must be some additional information and it must connect to the scenes in which the references are made. Reinforce the back-story, make minor characters stand out.

- One minor character per event

This one is the worst of the lot. It is similar to point 1 where we talk about minor characters being given unnecessary importance, with one important difference. Minor characters aren’t given importance, but there are truckloads of them.

While the reader is not misled into assigning undue importance to a minor character, he is however, completely drowned by the overabundance of minor characters. Keep an eye out for this problem because it creeps up on you and takes over your novel in no time. In YA novels dealing with high school or college you will find this problem when the protagonist gets the lecture time-table from a student counselor, buys some old books from a senior year student, gets a pack of beer with a student from down the hall, goes stationery shopping with the dork roommate and runs into the pretty girl from the Economics class at the store. You know these characters aren’t important and hence it’s all the more frustrating to keep hearing about more and more of them.

In my classes, I use an anecdote to drive home the (un)importance of minor characters. My late great-uncle was a very famous optometrist and would get about a dozen interns every year. Due to age or memory or plain rudeness, he would refer to them by number not by name. His defense: by the end of the year only 3 or 4 will remain, much better to just learn their names then.

That’s what readers want, that’s also what they do. They ignore characters till you say something that makes them sit up and look again at some character. Too many characters is like too much description, no one cares for it. At the very least, try to get a character to do more than one thing.

A writer must proactively search out minor characters and remove them. There’s a big benefit to removing excess minor characters, it often leads to deleting unnecessary minor scenes and makes your writing stronger.

- Passive supporting characters

Do not confuse supporting characters with minor characters. The protagonist’s friend whom he frequently turns to for advice is the supporting character, the guy who hands the friend a latte at the Starbucks is the minor character.

Drawing up supporting characters should be a post in itself, so let’s just look at the basics:

Supporting characters are not props.

Don’t take the qualifier “supporting” literally, most authors do. A supporting character is not just an agony aunt or a friend/mentor who spews life-lessons or smart-ass quips. A supporting character MUST support the story not the protagonist. It stands repeating: supporting characters must support the story.

Unlike minor characters, supporting characters need to do something other than run into Mr. Protagonist.

Supporting characters need to have a life and at least one subplot of their own. The closer the subplot is to the main plot, the better it is. By closer I don’t mean his actions have to help the hero, but they must have a bearing on the main plot. Let’s say your protagonist is working hard to save money for a surgery his daughter needs. The supporting character, a friend who has so far been helping the hero do that, decides to take a road trip to reconcile with his mother but meets with an accident. The protagonist pays for his friend’s bills and ends up with no savings. There you go, there’s the problem, there’s the tension and a possibility of high drama.

- Series characters

You are not a candidate for this last problem unless you are writing a series. Series spread over 3 or more books tend to have many characters, some of whom will be quite important. You cannot however introduce a character much earlier just because he is important. Characters must serve the story here and now. If you look at the Harry Potter series you will realize how important this rule is. Remus and Sirius play very important roles in the third book and they are friends of Harry’s parents but there is no mention of them in previous books because they had nothing to do.

This is what is known as Chekhov’s Gun. It’s a plot device named after the great Russian playwright who said: “If in the first act you have hung a pistol on the wall, then in the following one it should be fired. Otherwise don’t put it there.”

This works equally well for characters and is probably the single most important rule. Don’t introduce a character unless he is doing something right now. Imagine your ten-year old self being introduced to your future wife. Is she important? Yes. Do you need to know about her now? No.

You can also consider Chekhov’s Gun from the opposite perspective: If you fire a gun in the second act, then show it in the first act.

It works, sometimes wonderfully too especially if you connect back the dots and go wow. When important things are presented innocuously to the reader, they delight the reader upon revelation. It’s a common ploy in mysteries.

A word of caution: Many authors and writing coaches take Chekhov’s Gun literally and think that if something is not actually part of the plot it should be out. Consequently, they think of Red Herrings in mystery stories to be a violation of the principle. It is not.

Chekhov said that everything introduced to the author must do what it must and soon. The red herring is supposed to mislead and it will do that. It is not extraneous to the plot, it is the plot.

Characters must serve a purpose, they must do something to the story. Fiction has no place for bystanders.

Happy Writing!

I always love your posts, they are so cleare and to the point.

I’ve seen many of these problems, espeically when I was in a workshop (of course, tht’s what you’re in a workshop for, right) and (I’m sorry to say) in many self-published stories. And yes, as you said, it is frustrating, becuase quite a few of those self-pubbed stories had very good ideas that didn’t deliver.

Naming extras and giving them a basic background is the worst, in my opinion. And I’ve heard it many times on the workshop: it’s in order to make the fictional world richer.

Uhm… I thinkit just makes it more confusing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks.

Many writing coaches and authors endorse naming everyone and that’s the big problem. We have to ask, how many of the people we encounter everyday do we really know? We most likely don’t even know their names. To create something more realistic than the real world is plain indulgence. It doesn’t help the story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good points. There are so many works out there that could have been good if the author didn’t consider it done after the first draft.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks.

There shouldn’t be an entry barrier to getting your work out to the world but the lack of these barriers has also made rewrites and second drafts a thing of the past.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article, Anir. I’ve quoted it in my post this morning on weeding out unnecessary characters: http://tinyurl.com/nv7w4sk

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. Much appreciated.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Indie Lifer.

LikeLike

Much appreciated. Thanks.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on aspirewrite and commented:

The Basics of a Bad Novel – Characters

LikeLike

Thanks. Much appreciated.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on One Writer's Journey by Chris Owens and commented:

Reblogging this excellent three-part series of posts on bad writing and how to avoid it.

LikeLike

Thank you. Much Appreciated.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope it’s okay that I’m reblogging them, I think they’re very useful.

LikeLike

Oh, it’s absolutely OK and much appreciated.

LikeLiked by 1 person

An very useful and interesting article, thank you. I’ve been thinking of culling a few of the minor characters from my novel and now I definitely will.

LikeLike

Glad you found it useful.

LikeLike

This inotcdures a pleasingly rational point of view.

LikeLike

Pingback: No Place For Bystanders - Elizabeth Ducie: Author